There is a time-worn Peter Drucker quote about organizational development that goes “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. What he meant was that while corporate leadership would be pushing for strategic objectives, those strategic aspirations could be quickly and irreversibly undermined by wholesale failures of capacity, engagement or alignment by the vast majority of those who were supposedly being “led’. In the family work I do, I modify the old saw slightly to say: “Culture eats structure for breakfast”. I have found this to be one of the bedrock “truths” in working with families traversing generational transitions.

The Structuralist Assumption

In my experience, the overwhelming majority of professionals are fundamentally structuralists. I know because I was one for many years and my eventual conversion was a slow, hard-fought battle of awakening to a different, revolutionary perspective. Structuralists come armed with plans, strategies, solutions, best practices, and tactics. Trusts are established by lawyers. Financial plans are created by wealth managers. Tax strategies are developed by accountants. Business plans are promulgated by business consultants. Governance consultants help families draft constitutions. Family councils are established. Mission statements are drafted. Values are clarified and codified. Educational workshops for the “next gen” are held. All of it designed with the hope that these interventions at the level of structure will shape the future of the client’s life and trajectory of the client’s family. Entire industries are premised on this notion that the right structure, skillfully applied, will yield the right result.

Yet family culture all too often eats all this expensive structure for breakfast – and then spits out the bones.

Trusts fail and litigation ensues. Family behavior undoes financial plans. Tax strategies sit on the shelf because of lack of political will. Family feuds destroy otherwise healthy businesses. And the structural work of family governance specialists is a hollow shell that does not begin to address the family dynamics that, as it were, stand back, smirk, and then eviscerate all of this good work.

To make matters worse, family leaders are barraged by messages from these same structuralists that if only they adopt some new structure (a new form), their most pressing problems will be solved. The financial media reinforces this mainstream point of view with how people can fix problems through structural solutions. A brief survey of posts on Linked-in groups devoted to service professionals shows overwhelming advocacy for structuralist solutions. It is what sells. There is a lot of money to be spent in this land of structural solutions.

It is the grand assumption of structuralists everywhere that if one intervenes in a complex system to change the way the system is organized, that organizational change will change the behavior of the system and achieve better outcomes. This is the theory of almost all organizational change methodologies (of which 80% fall short of expectations). It is the bedrock of most social policies (80% or more of which fail) and it is the assumption of most family transition plans (80% of which collapse).

Why? Because culture eats structure for breakfast.

A lot of money and time is spent on these “solutions” for naught. Worse yet, families are left confused, disillusioned and cynical. As I survey the landscape, structural solutions simply don’t work to resolve the issues of complex systems let alone complex families. To paraphrase Jay Hughes, families are sold a lot of very costly forms that they cannot make function.

Structuralists, who don’t understand the power of culture, most often spend their professional lives rearranging deck furniture. Sometimes the ships they attend to happen to be headed on a good course and all is well. In these cases, it is wonderful to have well-organized, polished deck furniture and this ordered work makes the ocean passage much more pleasant. Yet for families unwittingly charting courses towards looming icebergs, the deck furniture is the least of their problems.

The Cultural Blob

There are families that spend 100s of thousands of dollars on high priced consultants to create family governance structures. These are the consultants who often create family charters and constitutions, mission statements, values documents, and family policies. This can be salutary if solid family culture exists, but very often they don’t work. In a project conducted by the Wharton Global Alliance, researchers found that the existence of family governance structures had virtually no impact on the existence of family conflict. [1] Their report states, “These results were surprising, as the formation of family governance institutions is considered to be a positive family practice that is supposed to facilitate family unity and to decrease family conflict. Our survey results suggest that the existence of family governance institutions, by itself, is not necessarily beneficial to the family in terms of reducing conflict.” The article goes on to speculate that better processes and more effective structure is the answer. That however is a conclusion not supported by the study itself. It is a study that is glaringly oblivious to the power of culture and is surprised that structure (and process) alone is insufficient to address conflict. This confirmation of the researchers’ structuralist bias – and the assumption that failures of structures are due to faults in the structures imposed – reflects a fundamental blind spot in many who address issues of cross-generational success.

There are families that spend 100s of thousands of dollars on high priced consultants to create family governance structures. These are the consultants who often create family charters and constitutions, mission statements, values documents, and family policies. This can be salutary if solid family culture exists, but very often they don’t work. In a project conducted by the Wharton Global Alliance, researchers found that the existence of family governance structures had virtually no impact on the existence of family conflict. [1] Their report states, “These results were surprising, as the formation of family governance institutions is considered to be a positive family practice that is supposed to facilitate family unity and to decrease family conflict. Our survey results suggest that the existence of family governance institutions, by itself, is not necessarily beneficial to the family in terms of reducing conflict.” The article goes on to speculate that better processes and more effective structure is the answer. That however is a conclusion not supported by the study itself. It is a study that is glaringly oblivious to the power of culture and is surprised that structure (and process) alone is insufficient to address conflict. This confirmation of the researchers’ structuralist bias – and the assumption that failures of structures are due to faults in the structures imposed – reflects a fundamental blind spot in many who address issues of cross-generational success.

So if this is true – if culture does eat structure for breakfast – then what is the answer? How does one change culture in wealthy families? To find the answer it is useful to look at the nature of family cultures.

Families are often “closed” systems. Families, in this sense, are “tribal”. Being tribal, families often operate in rote ways. They repeat mythic stories, each tribe member has defined roles, and the tribe operates out of these roles often in well-worn, almost scripted ways. Families enact and then reenact their comedies and dramas as they move forward – often with each comedy or drama having a similar feel to those that came before much like formulaic TV writing where every episode follows the same templated arc of development. These tribal systems are inevitably disrupted by key “kinship” events: marriages, divorces, births, deaths, sickness, youth, maturation, old age. In resilient tribal cultures, these events are culturally assimilated and in brittle cultures these events can fracture the unity of the tribe. In either case, the tribe adapts or simply falls apart.

Beyond this collective connective tissue of stories, roles and scripts, kinship relations are also awash with personality types, points of view, varying interests, history, psychology, parenting styles, learning modalities, family legacy, dreams, shadows, anxieties and a host of other “tribal” and archetypical characteristics. Tribal cultures are murky and tangled.

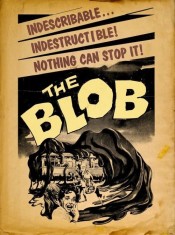

Most often very little of this complex dynamic is truly visible to the family. They “know” that this stuff exists intuitively, but they cannot articulate it or rise above it. Family members are “in” it. They feel the tidal tug of these things like primal and sometimes seemingly irresistable forces. They are acutely aware of the power at play in these dynamics. The family as a whole, however, has no way to make these patterns evident to the entire system. Even when certain individuals can see quite clearly core pieces of the dynamic, the problem is too big and too complex to address. All of this makes it very, very hard for families to change themselves without outside help. If everyone is in the system, every attempt to change the system is inevitably a symptomatic manifestation of that system. Even the efforts at reform are fatally infected by the same systemic themes they are ostensibly attempting to alter. This means that, like the 1958 sci-fi movie the Blob, almost all efforts to change are co-opted by a blob-like cultural dynamic of the family tribe.

By way of example, one family we worked with had a patriarch who wanted to intervene and guide his family through a process of collaborative decision making. His prior attempts were seen (quite accurately) as yet another way for him to control – or at least hedge – outcomes and that the invitation to “collaboration” was actually a thinly veiled attempt to get what he wanted which was for everyone to “just get along” in supporting his dream for the ongoing viability of his business, the cohesion of his family and his future legacy. His intervention, however well-meaning and altruistic, was itself a manifestation of an unhealthy dynamic and was sabotaged very quickly by the blob of family culture. This left him hurt, confused and quite baffled at the misfire. His efforts were actually simply another episode of a series of similar episodes of ineffective parenting that had stretched back for years. The rejection wasn’t even personal – it was simply his family culture doing what it does with him playing out his tribal role yet again.

This is why outside facilitation is so important for families. Family members that attempt to facilitate their own families will have those attempts consumed by the family dynamics, in large measure because those attempts at facilitation are actually themselves symptomatic of the family system. Most often families in the third or fourth generation have figured out how to use consultants and do so regularly. These families recognize that the “Blob” of tribalism in their family will devour their own attempts to change the system and that it is important to “bring the outside in” to disrupt the culture in productive ways.

Shifting Culture

So how do skilled cultural facilitators shift family culture? First, they pay a great deal of attention to the stories that they hear (and they hear a lot of stories). They look at the roles and scripts that are operating in the family. They suss out the rules of engagement. They pay attention to the patterns of family drama and comedy that play themselves out on the family canvas. They look at the kinship systems in play. They understand how the family has naturally adapted in the past. They pay attention to how power and love operates in the family. They look for anxiety patterns. They pay a lot of attention to alliances and splits. They are attuned to their own role and the ways in which they join and are becoming enrolled as participant observers in the family system. If this work is done well, this process of assessment can actually be used as a form of cultural intervention. If the facilitator asks questions in such a way that the system can be made visible to itself, the family begins to see itself in some new ways – it begins to make what is implicit explicit. In this sense, the tribe begins to wake up. But these types of questions – and the ensuing stream of inquiry from a stance of curiosity – can only be inaugurated from the outside.

What follows awakening inquiry comes facilitative design. While there is some science to this work, the design piece is far more art than science. This process is intended to generate cultural interventions that will positively disrupt the culture of the family. The work of helping family members see themselves and each other as adults, in adult-adult relationships, is vital to this process. Helping families tell new stories about the future and reframe old stories is key. Helping people try on new forms of action and adopt an open mind to experimentation is important. Creating explicit agreements is often useful (and this is structural work), not because the agreements will work – they usually don’t – but that, with an explicit expectation of failure, valuable insight and information surfaces as families confront their own performative contradictions. This is a period where polarities become visible: power and love, autonomy and belonging, activity and passivity, and so on. (One way to view “culture” is to see it as a snapshot of how any group of people is navigating core polarities at a point in time.) In short, this becomes a period of intense learning. It is also a delicate phase of the work.

This is a time where the facilitator and the family is most at risk. If the facilitator missteps, he or she can disrupt culture in ways that tip the family over into chaos. The family culture is finely calibrated to manage its stresses (however “dysfunctional” it may appear to the outsider) and interventions can easily create too much disruption. Finding the right inflection points and levering those carefully is tricky business. The wise facilitator is quite careful to lean back during this phase and deliberately look for only those changes that seem to be arising naturally. This is not visionary work – it is work close in arising from a kind of hyper-vigilance to the tolerances of the family system. The facilitator has a tremendous ally in the fact that families that choose to work with a consultant have a profound drive towards their own greater functionality. Working in flow with that drive (and not forcing it or rushing it) becomes critical. In doing this, the facilitator has to resist the family’s enthusiasm and desire for “quick fixes”.

The design work is thus fraught with ambiguity and complexity. For the family to trust it, it must come in containers that create integrity, confidence and hope. Family members must open to the process of cultural intervention. To get there, there must be quick “wins” – seemingly small changes that have disproportionate effects (what I have referred to in another post as “trophic-like cascades”). I have found that, with proper design and solid intervention, families have great wisdom in uncovering the right next steps for themselves. In this sense, it is the facilitator’s job to help the family find its own otherwise hidden wisdom.

As the process takes root, the shifting of culture emerges on many fronts in both individual and collective change. It happens at different speeds in different parts of the culture. In one family I have been working with a family member said recently “I have grown up with this notion of scarcity and what we are doing together is requiring a whole new way of thinking.” This is what cultural change looks and feels like – the slow emergence of a new way of being together. Different family members find themselves in different stages of this journey. For the cultural facilitator there is a complex balancing act. The work becomes a matter of hosting the right conversations at the right time and in the right order. It often has as much to do with slowing the process down as accelerating it. Most of all, it requires holding the entire culture with a kind of compassionate engagement that allows it to be as it is in a state of grace, but also an agility to intervene in ways that capitalize on what is emergent to help the family awaken and then live into its own future possibility. In this work, the cultural facilitator hospices the dying of the old world and helps to midwife the emergence of the new.

There is structural work that arises in this – and the structure can be important – but the real work has to do with shifting the culture. The consultants who do this work are few and far between. It is important for professional advisors to be aware of the difference between those who offer structure (and of their own biases to “results”) and those who can effectively intervene on levels of cultural shift. In the West we live in a world of structuralists. But as we all intuitively know: culture does indeed eat structure for breakfast.

__________________________

[1] See Wharton Global Family Alliance, 2012 Family Governance Report: Sources and Outcomes of Family Conflict. (Thank you Lisa Gray for forwarding this article!)

— December 1, 2014